Identifying and developing managerial competencies is an effective human resource management technique. Management competencies are also known as management skills. Due to the current dynamic development and changes, managers' personalities and competencies are receiving more attention. They are seen as essential sources of attaining a competitive edge for all managerial levels from low, and middle up to senior managers.

The production of organizational knowledge and its correct management will be the only sustainable competitive advantage in the future. Businesses and organizations are becoming more worldwide, which necessitates hiring international and global executives. There is a wide range of cultural variations among them from country to country. Hofstede and McCrae (2004) suggest a need to understand different cultural dimensions and their relation with managerial competencies in a global environment.

Understanding the possible links between knowledge, competencies, and cross-cultural management should be a deciding element in improving managerial performance. However, some problems are still to be answered, such as whether or not those managerial qualities are the same across cultures. How can we teach MBA students in foreign business schools how to acquire those managerial competencies globally? Even though business acumen and strategic skills must be acquired to be effective at the higher levels of management there is still a huge skills gap to be covered.

Previous research and literature reviews have found a strong link between knowledge management and both tangible and intangible organizational outcomes. The addition of managerial skills increases organizational outcomes. Management competencies are linked to managerial performance at work, according to Bartman (2005).

Related: Managerial skills: 10 crucial skills to build

Recent studies on managerial competencies in a comparative and cross-cultural context demonstrate that managerial competencies are roughly similar in importance across cultural situations. On the other hand, managerial competencies are likely to be influenced by status perceptions, the need for consultation, and the level of communication between managers and their subordinates - how good their communication skills both written and verbal. When evaluating and developing managers of various countries and cultures, these studies also highlight the necessity for organizations to identify the most stable technical talents from culture-sensitive interpersonal abilities. According to other research, there are three types of competency: external, interpersonal, and personal. This three-dimensional approach is consistent across nations.

What Are Managerial Competencies?

Advertisment

C H. Woodruff states that managerial competence is employed as an umbrella under which everything fits, including what may directly or indirectly relate to work performance. He defines it as "a collection of employee behaviours that must be applied for the role to accomplish the responsibilities emerging from this position competently." According to him, to complete their job, the competent manager must meet three basic parameters simultaneously.

These are to:

- have the necessary knowledge, skills, and capacities for this behaviour,

- be motivated to engage in this conduct and willing to put in the required effort,

- be able to apply this conduct in a professional setting and use emotional intelligence where need be.

The best contribution to understanding the notion of managerial competence and its practical application comes from R. E. Boyatzis. Managerial competency, he claims, consists of two components distinct from one another; a task must be completed in time - time management skills and the other is the set of skills that workers must possess to perform at the requisite level. Put another way, we discriminate between what we do and what behaviour is required to complete the task successfully.

According to S. Whiddett and S. Hollyford, Management team competencies are "systems of behaviours that enable individuals to demonstrate effective performance of duties inside the organization."

"Competencies are essentially the definition of expected performance," according to N. Rankin, "and should as a whole present a holistic picture of the most valuable behaviour, values, and responsibilities required for the organization's success."

According to some authors, management competence is defined as:

any individual trait that can be reliably evaluated or quantified and that can reveal a considerable distinction between effective and ineffective performance.

basic skill and facility are required for effective work performance.

All personal characteristics relating to work, knowledge, abilities, and values that motivate people to accomplish a good job.

Classification of Managerial Competencies

According to several scholars, the most frequently stated breakdown of managerial competencies is as follows:

1) threshold - the fundamental abilities and knowledge required to execute work, without which the employee would be unable to complete the task. In this instance, we cannot discriminate between great and average employees. To ensure the professional relationship and, interpersonal relationships are correlated with their capacity i.e. emotional intelligence. Unresolved conflict can affect relationships and have an impact on company culture, thus leaders must improve their conflict resolution and interpersonal skills.

2) commitment to high performance (divergent) - dedication to reaching high performance. Their goal is to highlight the distinction between great, above-average, and average employees.

Increasing efficiency can draw attention to the distinctions between exceptional, above-average, and mediocre employees. According to Krajcovicovas, Caganova & Cambals (2012) perspective, employee performance can be improved if employees' requirements and development needs are appropriately identified and appropriate educational initiatives are implemented. Their paper divides managerial skills into three categories: general, specific, and critical (crucial). Their classification of managerial competencies is based on above-average managerial performance as the primary criterion.

- General managerial competencies, which every manager should have, can give quality work performed in any management position.

- Specific management competencies will include the managerial competencies needed to fulfil the standard performance for a particular management position.

- Key management competencies are those to which the manager gives increased importance and enhances employee performance.

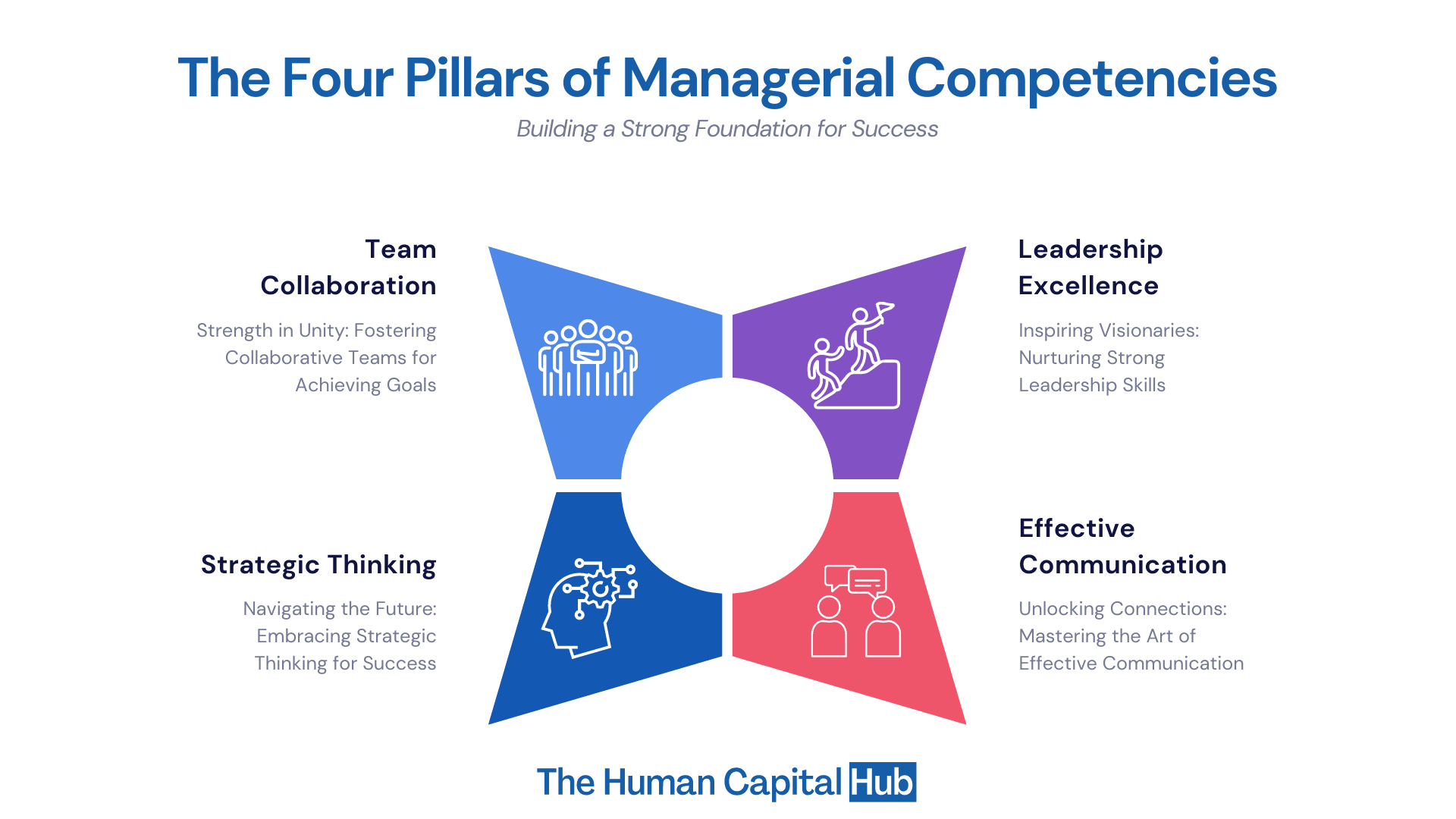

The Four Pillars of Managerial Competencies

If you are or plan to be a manager in your organization, you must understand the 4 Pillars of Managerial Competencies.

The four pillars do not stand alone but are part of a larger totality. They are:

- Knowing the Organization

- Leading and Managing People i.e. human resource management

- Managing Resources

- Communicating Effectively i.e. communication skills

Knowing the organization entails understanding current rules and procedures to guarantee those unit activities are efficient and in line with the organization's overall objectives. This pillar contains policies, procedures, vision, mission, goals, strategic plan, and other competencies.

Leading and Managing People requires honing your ability to provide criticism and guidance to employees, ensure customer satisfaction, and foster a collaborative environment. Performance evaluation, staff development, team building, collaboration, customer interactions, and other abilities are all included in this pillar.

Managing Resources concerns understanding the tools and processes for planning to meet specific goals and place efforts in the larger context of strategic initiatives. This pillar encompasses abilities such as planning, project and budget management, information management, change management, organizational performance evaluation, and so on.

Building skills to encourage seamless and fulfilling interactions among staff and consumers is part of Communicating Effectively. Meeting management, listening, constructive feedback, effective presentation, written communication, and so on are required skills.

Competency Models

The availability of competency models to aid in designing training and development activities for recruits. A competency model is created due to the identification of managerial competency requirements. A competency model is a set of skills that, when combined, determine successful performance in a certain workplace. It serves as the foundation for evaluating job performance and determining career paths. This list of managerial or leadership competencies in a competence model for firm management comes as a complete shock. Its job is to find discrepancies between what the organization says, what they anticipate from their employees, and what they require. Competency models can be created for specific jobs, and job groups e.g. a leadership team, organizations, occupations, sectors, etc.

A competency model is a set of knowledge, skills, and other personality traits that describe a specific mix of information, abilities, and other personality traits. They are required for the organization's tasks to be completed efficiently with the individuals acting as a role model to others within the organisation.

Competency models come in a variety of shapes and sizes. As a result, the construction of a competency model mainly depends on the company's goals and objectives. A model's competencies can be grouped in a variety of ways. There is no one-size-fits-all solution. Instead, the best structure will be determined by the company's demands. A popular strategy is to select a few cores or critical talents required of all employees and then a few other categories of competencies that are only applicable to specific subgroups. Some competency models are grouped by competency types, such as leadership, personal effectiveness, or technical capability. Other models may use a job-level structure, with a core set of competencies for each job family and additional competencies added cumulatively for each higher job level within the job family.

Conclusion

Managerial competencies are a beneficial complement and augmentation to the traditional performance management process, benefiting both the person and the company. The assessment offers employees information on how their skills support and contribute to the organization's success and a framework for planning learning and development in their current role and promotion within the company.

The assessment of competencies can provide valuable insights into the organization's skills and talent pool and the competency gaps that need to be filled to fulfil current and future needs.

Milton Jack is a Business Consultant at Industrial Psychology Consultants (Pvt) Ltd, a business management and human resources consulting firm.

LinkedIn: linkedin.com/in/milton-jack-9798b966

Phone: +263 242 481946-48/481950

Mobile: +263 774 730 913

Email: milton@ipcconsultants.com

Main Website: www.ipcconsultants.com.